by Noah Dillon

Accumulation can be a really powerful force. Think about the early universe: it was all indiscriminate proto-matter, not even particles. Then, as things cooled they started to clump together, and after just a few billion years we get all the diversity of planets, star systems, life, nebulae, and so on that can be seen from a backyard or a rooftop on a clear night. Or, thinking even more locally, an island as part of an atoll, a grain of sand as part of a beach, a person contributing to a community, a dot in a halftone photo, a thought as part of an ideology.

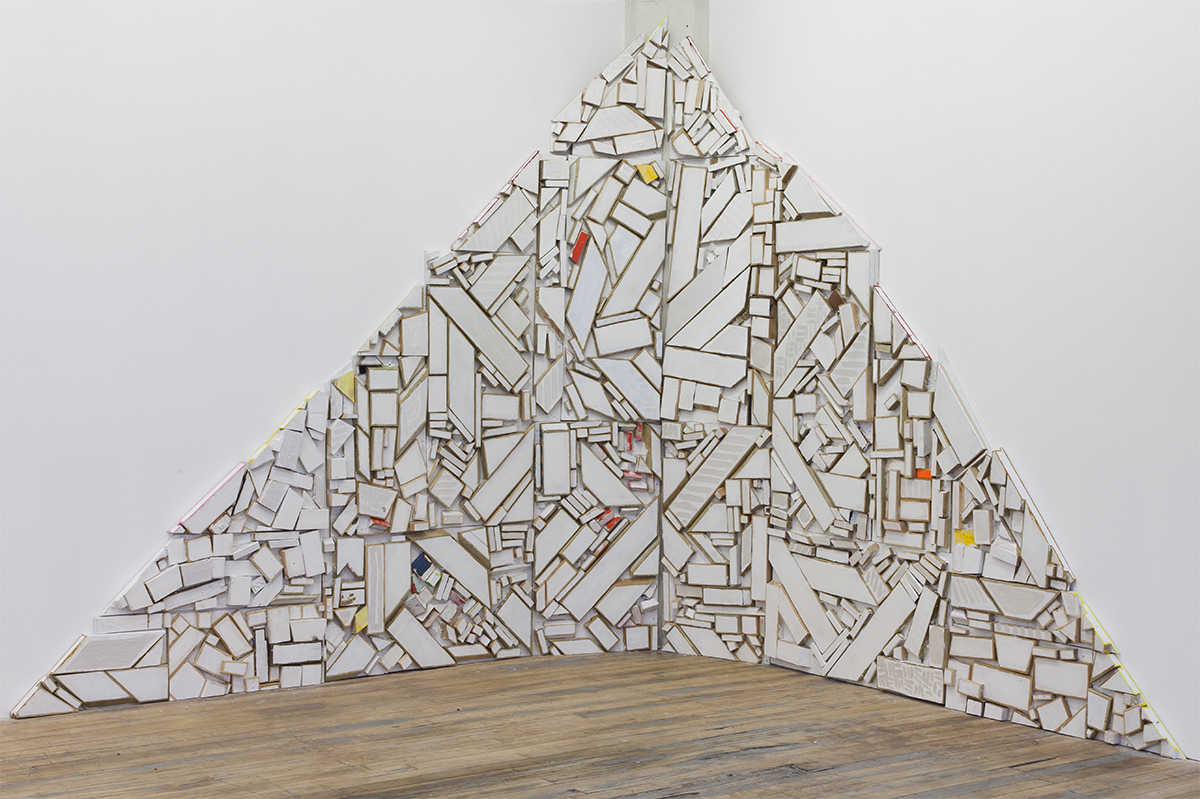

Cordy Ryman, “JoDeck Mountain,” 2013. Acrylic, enamel, shellac on wood, 232 x 118 x 2 1/2″. Courtesy of the artist and DODGE gallery. Photo by Rachel Styer.

The skirtlike JoDeck Mountain (2013), by Cordy Ryman, which drapes down the corner of a wall, is exemplary of just such accretion as force. Receding as it does into the vertex, it nonetheless builds and crescendos. Its mass is secondary to this effect. The mountain is nearly flat against the surface of the wall and does not project outward. Its construction is modular, though largely unseen. It is a peak of negative space, really. But the tightly arranged wooden mosaic is monumental.

The surfaces of the small, irregular pieces are painted almost all white with acrylic and enamel, highlighted by spots of fluorescent pink and bright, lemony yellow dispersed lightly throughout. The reflected light from those bits of color give the hill a sense of glowing, growing momentum, and project it out into the space of the viewer. Approaching, one is hesitant to intrude too much into the space that it seems to occupy. It is a mountain, and has the concomitant affect of sublimity. Getting in close you risk being swallowed up in light and matter. Ryman has experimented with color extensively, and his reductive pieces—using reflected light to cast glowing tones over the white surfaces—are where he particularly excels, where he can build a universe from accreted atoms.