by Eric Sutphin

People say “once an adult, twice a child” as a pejorative for aging but Jonas Mekas has always possessed a child-like curiosity that has propelled his remarkable approach to filmmaking. Mekas is now 91 but in his nearly seven decades of making films, photos, collages, and performances, the artist never succumbed to the deadening of his pleasure with the world around him. In a short film diary he made of the Surviving Sandy exhibition, he points his camera at the screen that is showing his film Walden made in 1969 and chuckles at the younger Mekas (also holding a camera) as if seeing an old friend.

Mekas’ films unfold as multifarious tapestries, moving collages. Mekas possesses the uncanny gift of making film physical.

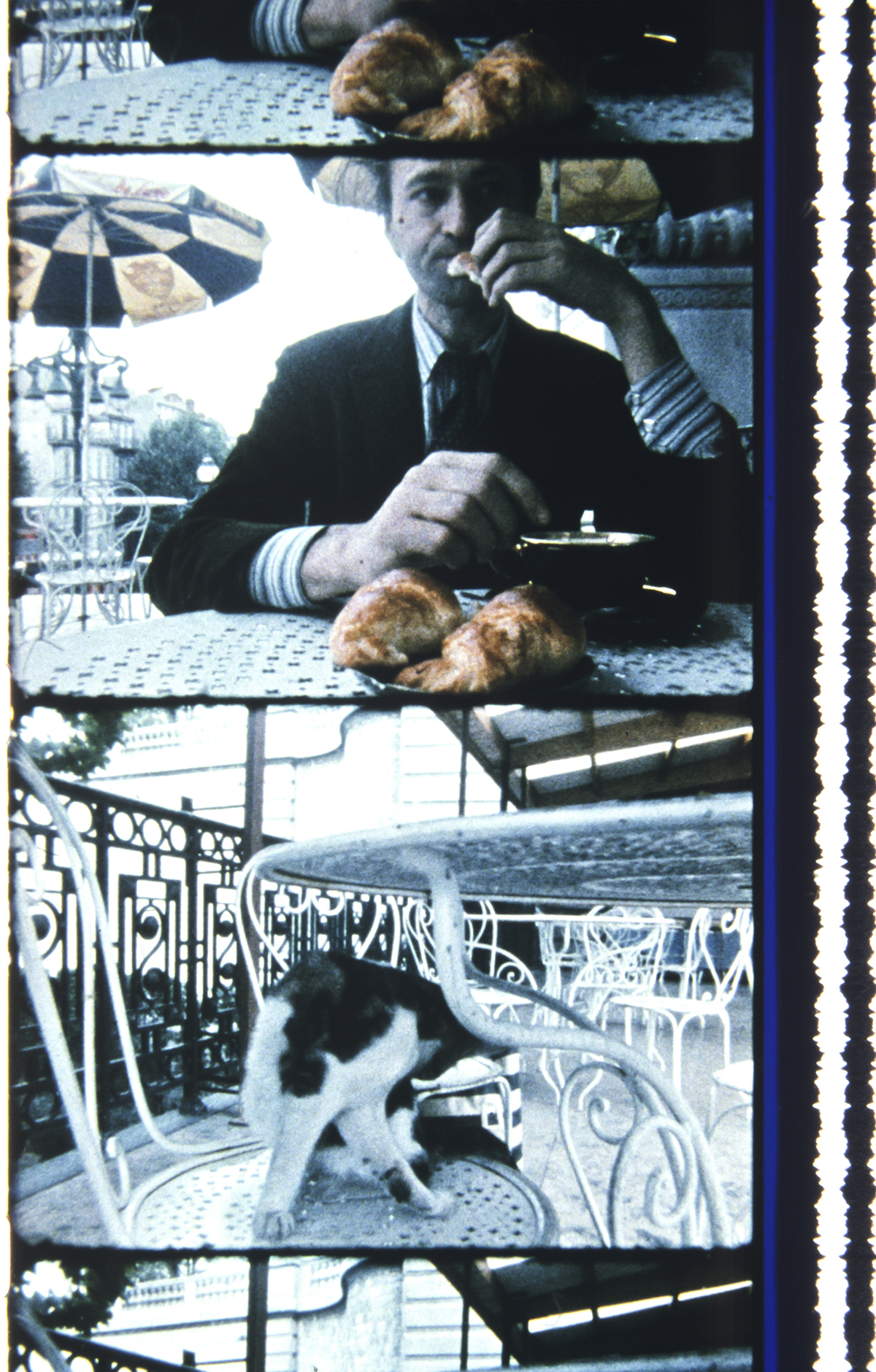

Mekas has assumed a position as an icon of avant-garde film across generations. He is pals with Harmony Korine, is said to have convinced Warhol to make movies and is a favorite of Hans Ulrich Obrist. Mekas’ monumental filmic endeavor Walden is composed of hundreds of scenes that were taken by the artist daily with his Bolex 35mm camera in the mid 1960s. This non-linear narrative, a diaristic exploration, premiered at the Elgin Theatre on West 19th Street in 1969. Coming out of the generation of Happenings and Fluxus, Mekas’s films unfold as multifarious tapestries, moving collages. Mekas possesses the uncanny gift of making film physical. The camera is an appendage but instead of creating distance, the lens and reel transmits the sensoria of the everyday as if unmeditated by Mekas. This is the genius of Mekas, he brings himself—and us—closer than we could ever be with the people and environments he films. These images (a wedding party, a picnic) collect a patina and become oxidized by art history (a dejeuner sur ‘l’herbe peopled with downtown denizens of the avant garde) and are reconfigured so that we might again enjoy the humility and humanity of these classic forms. Walden is an epic-length study in the delights of the physical world, which are threaded together in a collage of fractured, flickering celluloid frames. While the images register as “real” the film itself becomes a gestalt of the everyday sublime. In this way, Mekas is essentially a Romantic. His films may not narrate but they tell stories which begin with the specific and swell out into the universal. We might watch several minutes of an inchoate sequence (shaky, harsh background noise, undefined forms) but then the eye trains itself on a face, unaware of the camera, and we are brought into relation with a moment upon which the entire film seems to pivot. But these pings of recognition fade again to nonspecificity until the eye/the camera trains itself again on an object of momentary reflection. This process goes on as Mekas wanders, always looking, tender and curious. Though Walden presents us with a diary, Mekas sidesteps solipsism and gives us his generosity. Each frame of Walden is a little treasure.