by Maya Harakawa

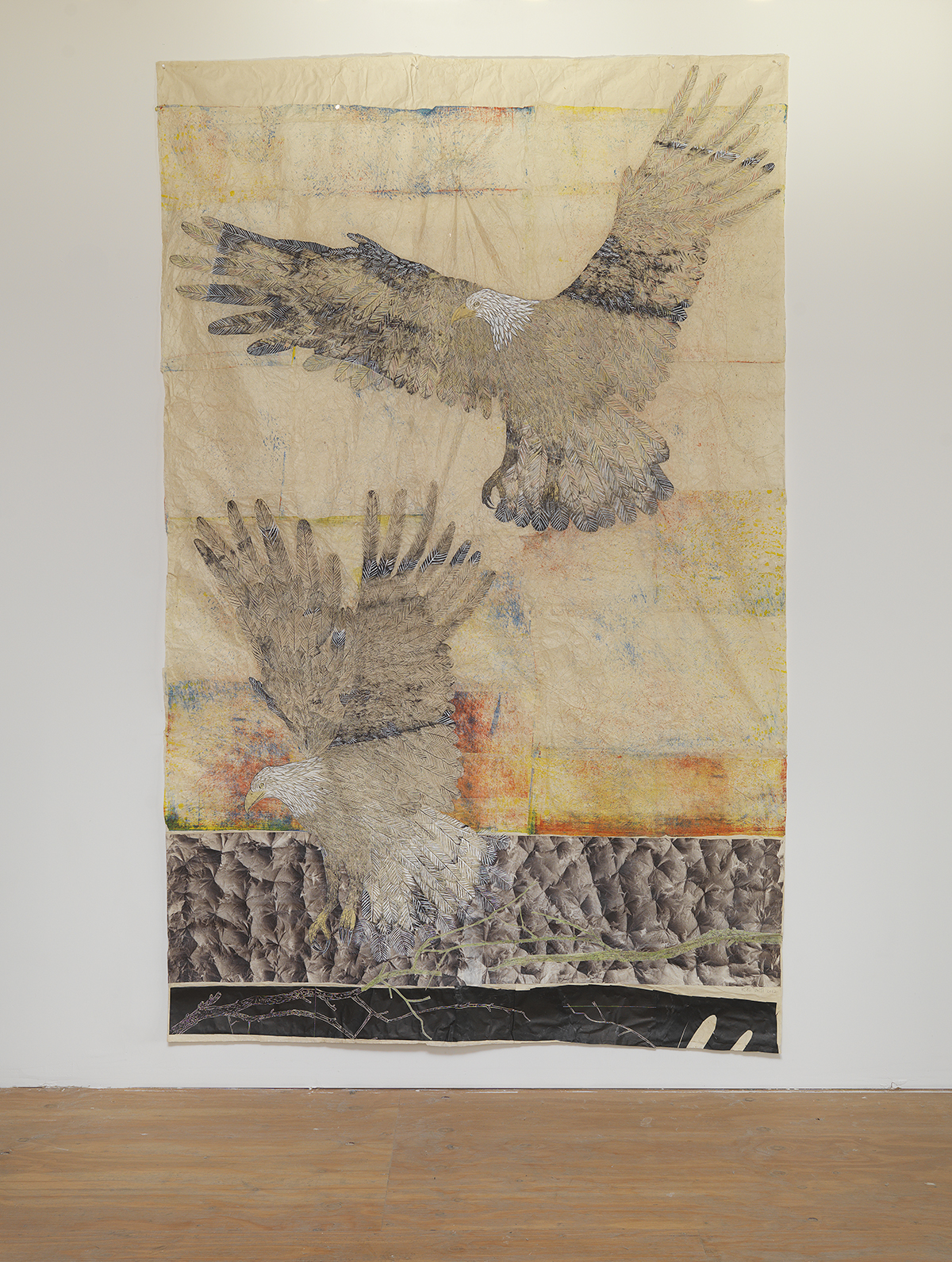

Kiki Smith has a way with wonder. In her careful yet playful depictions of the natural and the fantastic, she occupies pictorial space with a cast of characters whose relationship to reality is delightfully ambiguous. In keeping with this embrace of the almost possible—as opposed to what is simply familiar—narrative is often left open: momentary and often without contextual explanation, her works demand elaboration. And yet, even as they raise questions, there remains something concrete and constant in the material properties of works such as Cathedral and Guide. Both are marvelously tactile: the hand of the artist is always present in the idiosyncratic lines that populate them, and the delicate paper on which they are executed begs to be touched. So while these works on paper can, of course, be described in formal or compositional terms, they might best be described with a gesture, say the unspecific but nonetheless sensually connotative act of rubbing one’s thumbs and fingers together. In other words, viewing these works produces a physical response.

What does it mean to view tactility and use the eye to enter the realm of touch? Meaning as significance and definition, seeing as viewing and understanding, and feeling as touch and emotion: Smith’s art fosters an encounter predicated on the slipperiness of these words. Their meanings overlap and do not necessarily assert their distinction as they play off of and with one another. As literal meanings proliferate, they become glutinous: they stick to each other in the various and unpredictable permutations that then ask a set of newly derived questions. What is the significance of understanding touch? What is the definition of seeing emotion? And so on and so forth, ad infinitum. In struggling to fully comprehend the eagles or the wolf—their story, their purpose, their world—the processes of seeing-feeling or understanding-touching reveal new channels for interacting with these works as sites for sensory exploration. As one sees the remnants and past physical activity, the body and the mind recollect, responding to a reworked topography of the senses drawn from previously embodied knowledge or emotions which are called upon to react anew in the present. To ask the question of visual tactility is then to explore the body’s capacity to travel and be traveled in unexpected ways that produce the unpredictable yet familiar effects that we come to understand—but not always fully articulate—as a response.