by Gaby Collins-Fernandez

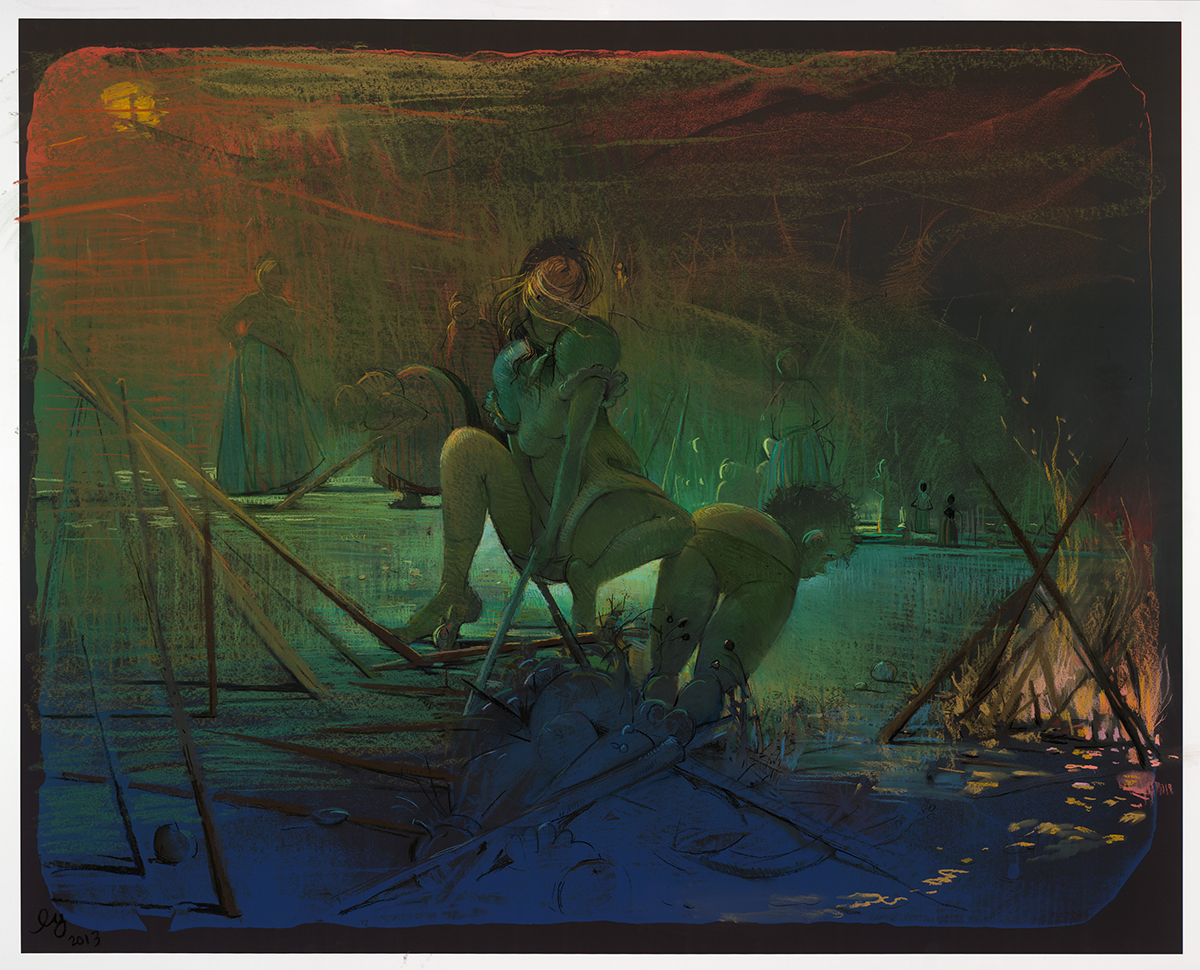

Lisa Yuskavage’s two Surviving Sandy monoprints with pastel additions treat young, nubile figures in relatively isolated landscapes. A No Man’s Land 2 is the more narratively obscure of the two. In it, a squatting young woman appears to be making a bonfire like the one already lit to the right of the piece. She wears a briefer version of the garments donned by the groups of sternly dressed peasant-types in the background. It becomes apparent that the pile of sticks in front of her is also a pile of women, one on her hands and knees, and another whose blue legs masquerade as firewood. While the squatting young woman appears totally engaged in her task, the roles of the other two are less clear: their positions alternately evoke a sense of kinky role-play, their own disorientation, and the sense that they themselves are to become a pyre. The uncertainty of the squatting girl’s relationship—benevolent or not?—to these other two heightens the possibility that she might light them on fire; the centrality of her position and the neon halo behind her torso cement the sense that she is in charge.

The primary subject of Neon Sunset is a revisited figure, notably from Walking the Dog (2009) and Triptych (2011). For Neon Sunset, Yuskavage drops her—legs splayed, socks connected, sucking a lollipop or her finger, and unself-consciously spacing out—into a valley. Backlit by the aforementioned sunset, the girl takes on the monumental quality of the mountains around her; the scene pictorially and psychologically emanates from her crotch, as though the force of her reverie were fecund enough to push the whole scene out from her vagina.

Like in A No Man’s Land 2, the sexualized connotations of the young protagonist’s body—her pose, ball-like buttocks, sucking gesture—are immediately present in a way that belies the ambiguity of the piece’s internal logic. The connotations loiter around the experience of the work much like a marmish woman does in the background, hands impatiently at the waist, keeping guard or passing judgment. Still, causality in the narrative is particularly mysterious, as questions of what the figures are doing in the valley, what society they are a part of, or how they relate to each other are not obviously addressed. One of the tensions of the work is the contrast between how quickly the girl provokes ideas about sex, power, and gender and how long it takes to engage with the presented narrative—that is, to actually look at the work—while keeping one’s own opinions about these at bay.

In this light, Neon Sunset can be read as an allegory of at least five modes of looking at young girls in art: 1) the inquisitive look of the art viewer; 2) the juicy glances directed toward juicy young bodies; 3) the judgment-laden and distrustful regard that society reserves for young women who flaunt their nubility; 4) the actual gaze of the marm-figure upon the girl; 5) and the inward gaze of the girl’s musing, directed away from our probing, the marm, and anyone else who may be watching.

As in traditional allegorical painting, the setting is a conceptual, propositional space rather than a reference to an actual location. Here, it becomes the site where all the gazes, except the girl’s, meet. Although she is their catalyst, the young girl is too wrapped up in her own thoughts to deal with them. And who would want to? In their theoretical proximity, these ways of looking become more dissimilar and dauntingly difficult to respond to all at once. It becomes clear that they do not resolve, and that the structure of the painting exists to hold them all in one place.

Yuskavage has suggested in interviews that one can read the structure of her recent paintings psychoanalytically, the young women and supervising background figures stand in for the id and superego of the work’s consciousness, while the painting itself is personified within the work as one of the young female figures. Aside from the radicality of endowing painting with the consciousness of a young woman without shying away from her interior dramas or the external expectations and consequences of her appearance, this might allow us to view the scene depicted in Neon Sunset as an extrusion of the girl’s own mind-space, activating her role as processing the same conflicted ways of looking the audience engages in. Likewise, A No Man’s Land 2 can be read in terms of its combustibility: rather than pose a threat to any of the figures in the foreground, the fire becomes symbolic, a force of the power and potential destructiveness of the young women’s intensity.

After all of this is said, what is left is to continue looking. The prints remain very honest and very tender. The work’s inclusion of various, contradictory modes of approach as part of its own framework is especially generous because the subject matter is the psychology of young women, for whom the issues of socially expected sexualization and complicated gazes are routine intrusions. The slowness required to parse Yuskavage’s narratives allows the audience to look at the quickness of our own associations, and in doing so to approach both these narratives and our first impressions with less judgment and more empathy.