by Juliet Helmke

Juliet Helmke: I visited your works a few times at Surviving Sandy, but it always took me a while to get close enough, I had to wait for a moment that was completely my own. I heard a lot of people discussing where they had been painted, and a fair number of visitors, not seeing the titles, confidently identified the locations as close to where they lived or worked, and yet, they were completely wrong.

Rackstraw Downes: I actually got compliments from people who I thought would not normally go to that show, but they went and saw my work and thought it was well installed and looked beautiful. I was really pleased, though I didn’t get to see it installed. I spend about half the year in New York and the other half in Presidio, Texas. I got an invitation to lecture in Galvaston, Texas, and when I went down there I was just fascinated that there were all these oil rigs out there on the horizon, out on the ocean, and these flat level areas of marshy ground where these oil pump jacks and refineries were, and I thought, this is for me.

Helmke: Do think there are places where you couldn’t move to? Even if the weather was right and the seasons made sense?

Downes: Probably there are plenty of places I would put on the list that might be climate right but imagery-wrong. For instance, I remember years ago in the 1970s I was invited to work for the Department of the Interior to make paintings of images to do with the various industries that the Department of the Interior oversaw. They called me up and told me a few of the locations, saying, “well, you could go to Cape Cod, you’d love that… and then there’s Pittsburgh, where the Bureau of Mines is headquartered, but you probably don’t want to go there.” And I said “Quite the reverse! I want to go to Pittsburgh. For my work, the prettiness of Cape Cod is too rehearsed and familiar!”

It’s very important for me to be in my environment when I’m painting. If I’m painting the city I need to be in the city.

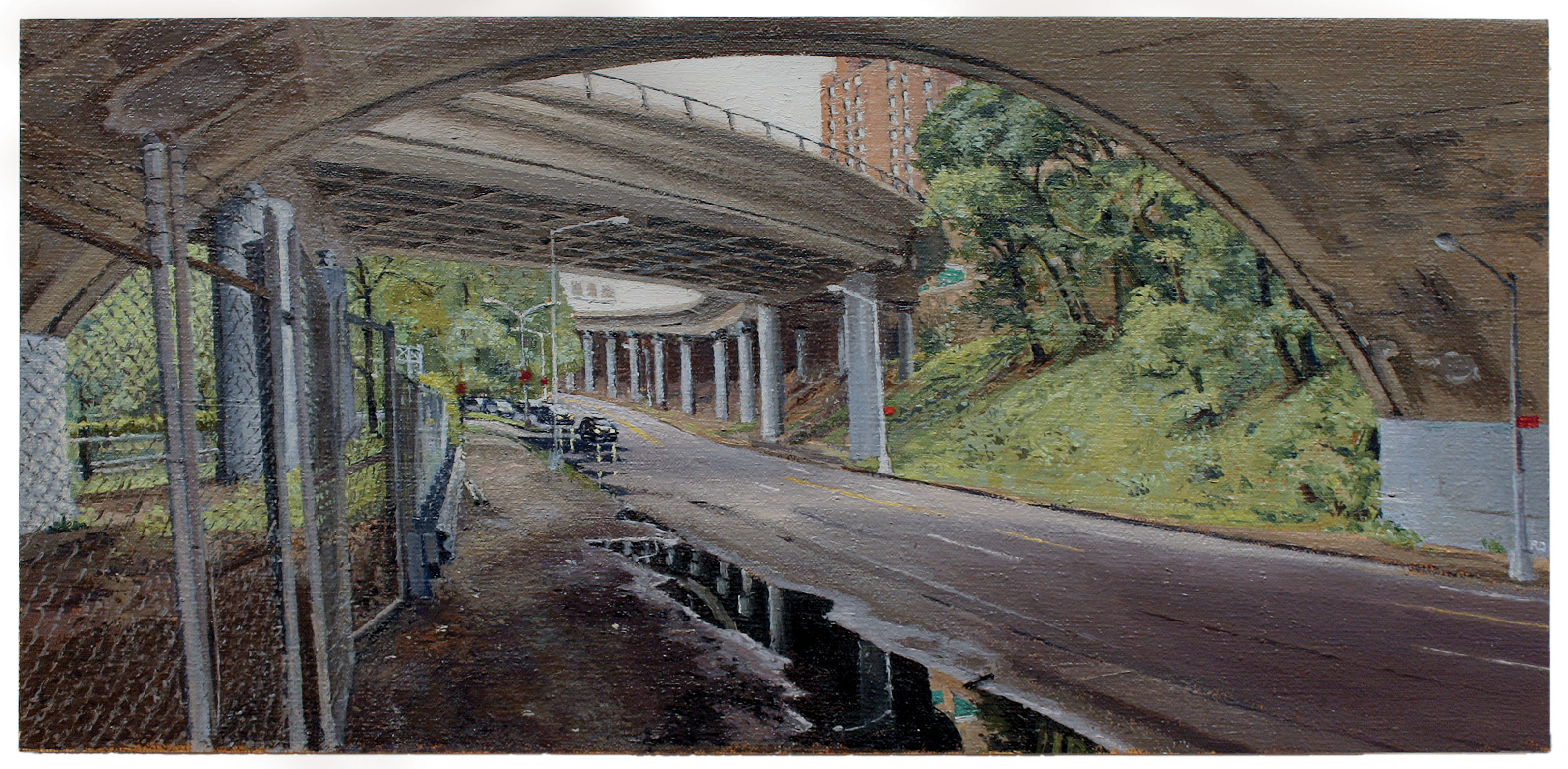

Helmke: It’s interesting that you use the word “familiar” because that is what you paint, but the scenes are not familiar in the beautiful way, they are familiar because they are overlooked spaces, places that are passed by or passed over. You render them with exquisite precision—the side of a highway, or underneath a subway overpass, or while perched on the edge of a bike lane, or nearby a public housing development in Harlem. You pay attention to the streets we use on a daily basis, the sidewalks, throughways, subway tracks, and power lines—things that we usually pass without noticing, but that we were suddenly very aware of when they became unavailable due to flooding.

Downes: I have things to say about those places, too. For example, I think many of us wish or imagine that the landscape could be better looking if you could get rid of that power line, but we’re not willing to give up our refrigerators, which we would have to do without the power line. I’m trying to tell the people not to fool themselves. If you really want to get rid of power lines than get rid of your fridge.

Sometimes I keep a journal when I’m painting, and I will note down the things people say as they pass by. I did that with the painting that was done by the projects, George Washington Carver Houses 102nd St. Between Park and Madison (2008). Gradually I began to populate that painting with people I heard passing by. For instance one said, “Oh look he’s got people in there now!” And another lady said, “I see a nurse!” And I thought that was such a strange remark, but then I realized of course that where I was painting was on the way from the subway to Mount Sinai. I realized that that’s what she was commenting on because she was used to seeing people from the hospital in that area.

Helmke: It’s wonderful that people can look into your work and craft for themselves what’s going on. I had that experience. The work was very personal to me. It was like I was looking at the changes in my environment after Sandy.

Downes: It’s very important for me to be in my environment when I’m painting. If I’m painting the city I need to be in the city. I’ve painted from windows before but that feels very detached so that doesn’t really do it for me.

Helmke: So you are making the people in those neighborhoods a little more aware of their surroundings while they watch your painting develop from day to day. Not a lot of your paintings have people in them.

Downes: Often they don’t, that’s quite true. But in that group of paintings there were people. Quite a lot of people in Under the J-line—cops, bus drivers, you see the guy who does the timing of the buses talking on his cell phone. I have a lot of fun with those things. They’re very tiny details. I’m a great fan of Claude Lorrain, the famous artist from the 17th century. Lorrain used to say “I sell my paintings, but I give away the figures in them.” They were very important to him, as they are to me. I recently published a book in which there were two essays on Claude Lorraine. Both of them have to do with examining what is going on with the figures in the painting and how the landscape forms itself around that situation. This also happens a little bit in my paintings in the show. You’ll see in Under the Westside Highway at 145th Street: The Bike Path No. 1, there are three figures coming along on bicycles on the path. And a little bit ahead of them there’s one woman running. Maybe she’s running away from them, maybe they have nothing to do with each other, but it pleased me enormously to have that situation in there. It was like something out of Ovid.