by Samuel B. Feldblum

Part of the charm of New York City is the alien aspect of much of its setting: still relatively recent in historical terms, this artificial landscape remains a strange scene to behold. Even the trees dotting avenues and small parks are curated, nature now just another tool that we use in our efforts to make the world in our image. But if Sandy was a reminder of anything, it’s that nature is not our plaything, and rather than fitting her into our designs we had better fit into hers.

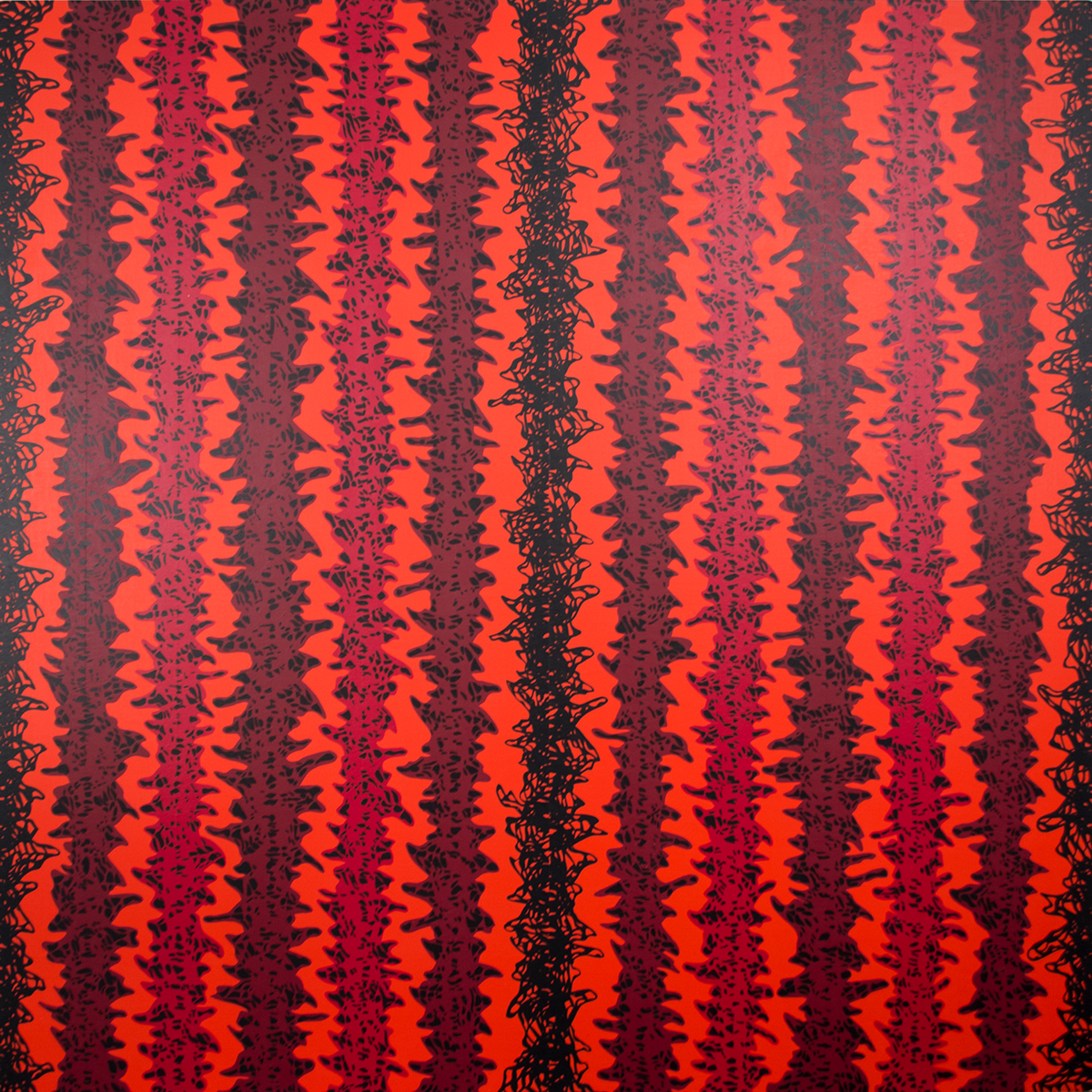

And though our relationship with the earth often takes a frictional tack, we are indeed a part of nature, bound by its laws and by its energies pulsing through our environment. Katia Santibañez’s work focuses on these energies. When she was just beginning to paint, gardens in the French countryside served as her inspiration; later, the shapes and spaces of Paris and New York became her muses. Trees and facades, grasses and their shadows, geometric architectural motifs all fold into her oeuvre. She mentions as inspiration for more recent work the grid of New York City seen from above, the rectangular facades, the clashing of horizontal and vertical forces everywhere, all of which combine in her work to create the lattices and lines of Shadows upon Shadows and Between the Waves. But underneath the fraying regularities of these paintings lurk hints of our chaotic environment, ever-present and rushing through gaps and cracks in the more patterned mien. The artificial becomes wilder, the natural more serial. Cityscape and landscape converge.

In Shadows, charcoal bars scurry crookedly across a black background in rows. The painting is as much a nocturnal walk through canopy-darkened Appalachian woods as it is a shambling through the late-night streets of New York City—especially when the lights go out, as during Sandy. A night-shaded straw fence is suggested too, flimsily attempting perhaps to separate the outside world from our more organized plots. We are lost somewhere. Duality reduces to totality: we see that we are not separate from nature, just a source of sometimes-discordant notes in her larger harmony.

Sandy did nothing to change this conception of the relation between nature and man. She only reminded us that despite our attempts to insulate ourselves in worlds we design, our world is not our own.